What are AGEs and why are they important when it comes to healthy aging?

Explore the significance of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and their role in health, well-being, disease prevention and aging.

February 08, 2024

6 min read

The ability to influence health through lifestyle practices that promote healthy aging is an ongoing topic of interest. Many behaviors that promote good health have gained attention, and consuming a sound diet is one of the most important. When considering dietary factors that have an influence, advanced glycation end products (AGEs) are emerging as an important area of focus.

What are Advanced Glycation End products?

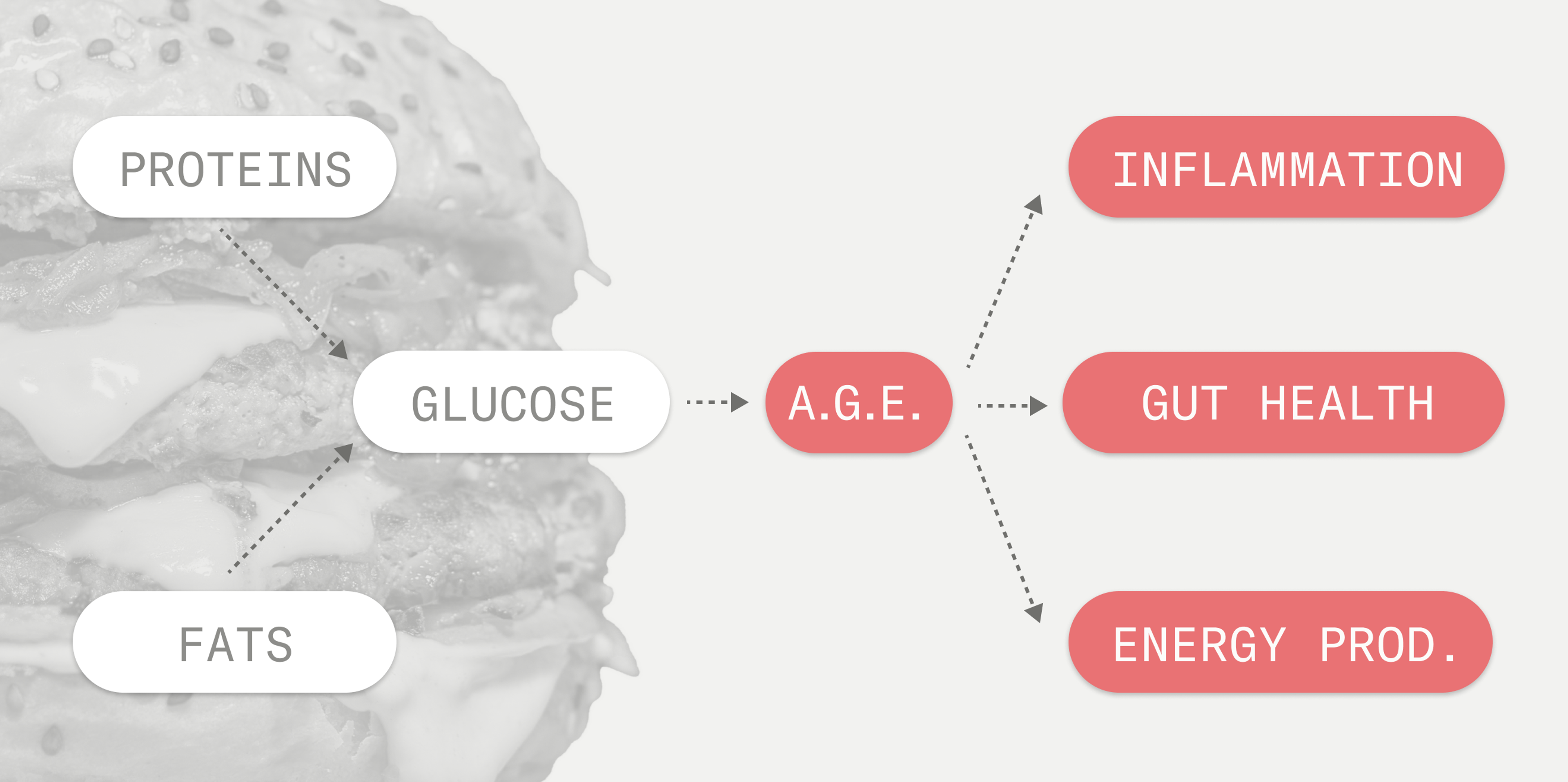

AGEs are potentially harmful compounds that are formed in the body when proteins and fat combine with sugar. They naturally build up in the body with age and are both produced in the body and formed through exposure to different substances. It is likely that the AGEs that are formed due to different exposures create more health problems than those that are produced in the body during the normal aging process, as the amounts are generally higher.[1]

Where do AGEs come from in the diet?

While AGEs can be produced through exposures such as alcohol and cigarette smoke, the diet is an important contributor as well. AGEs are widely found in foods, particularly those that make up the Western diet. In general, meats contain the highest amounts of AGEs per serving, while fruits, vegetables, and whole grains have lower amounts.[2]

Dietary exposure to AGEs

Food manufacturers add AGEs directly to foods to improve their appearance and taste.[3] They are present in fried and processed foods, including those such as soft drinks containing high fructose corn syrup and/or sugar.

The formation of AGEs in food depends on factors such as temperature, water content, pH, and cooking time and method. When we cook food and it browns, like they do in baking, grilling, searing, and frying, a reaction called the Maillard reaction occurs. While these types of heat treatments are commonly used to improve flavor and texture, as well as extend shelf life and enhance food safety, this reaction also creates AGES[4]. While AGEs are present naturally in items such as uncooked animal-derived foods, their amount significantly increases with processing and cooking techniques.[5]

Some of these cooking techniques have become more popular due to the demands of our current environment. Stressful and busy work schedules cause us to turn to prepared and processed foods, which generally contain higher amounts of AGEs compared to home-cooked meals. These include convenience foods such as cookies, biscuits, and chips.[6]

Avoiding AGES in foods

Certain cooking techniques may prevent the formation of AGEs, however. Some examples of these are cooking with moist heat, using shorter cooking times, cooking at lower temperatures, and using acidic ingredients such as lemon juice and vinegar. The type of fat used may also make a difference. Cooking spray, margarine, and oil have been found to result in less formation of AGEs than the use of butter.

A reduction in intake of AGEs may be achieved by consuming a diet containing fish, legumes, dairy, vegetables, fruit, and whole grains and reducing intake of solid fats, fatty meat, and highly processed foods. These guidelines align with general recommendations for a healthy diet and disease prevention.

Why are AGEs important when it comes to health?

AGEs have a pro-inflammatory effect in the body and promote oxidative stress, which negatively affects tissues in the body.[7] Inflammation is believed to play a crucial role in driving chronic disease and aging. Long-term exposure to inflammation may leave the body in a constant state of activation that increases disease risk.[8]

AGEs may also have a negative effect on gut health, as they may cause changes to the gut structure that lead to dysfunction. Given that many dietary AGEs cannot be absorbed in the small intestine, they also pass through the large intestine, where they are partially broken down. The presence of AGEs may result in changes in the microorganisms found in the gut that may negatively affect health.[9]

Research has shown that AGEs may be implicated in the development of several chronic diseases, including cardiovascular and neurodegenerative disease, diabetes, and skin aging. One of the reasons for this is that accumulation of AGEs leads to dysfunction of the mitochondria, which are considered the “powerhouse” of the cell. This may result in impairment in energy production and problems such as a decline in cognitive, immune health and age-related chronic conditions.[10]

Understanding the role of AGEs in our diet and their impact on our health is crucial in the pursuit of healthy aging and disease prevention. While AGEs are a natural part of aging, their excessive accumulation through dietary sources can accelerate health issues and contribute to chronic diseases. By making mindful choices in our diet and cooking methods, we can significantly reduce our exposure to these harmful compounds.

Embracing a diet rich in whole foods like fruits, vegetables, legumes, and whole grains and adopting healthier cooking practices not only minimizes AGE intake but also supports overall well-being. As we continue to navigate the complexities of nutrition and health, being aware of AGEs and their effects empowers us to make informed decisions for a healthier and longer life

References

- ↑

Rungratanawanich W, Qu Y, Wang X, Essa MM, Song BJ. Advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and other adducts in aging-related diseases and alcohol-mediated tissue injury. Exp Mol Med. 2021 Feb;53(2):168-188. doi: 10.1038/s12276-021-00561-7. Epub 2021 Feb 10. PMID: 33568752; PMCID: PMC8080618.

- ↑

Uribarri J, Woodruff S, Goodman S, Cai W, Chen X, Pyzik R, Yong A, Striker GE, Vlassara H. Advanced glycation end products in foods and a practical guide to their reduction in the diet. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010 Jun;110(6):911-16.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.03.018. PMID: 20497781; PMCID: PMC3704564.

- ↑

Turner DP. The Role of Advanced Glycation End-Products in Cancer Disparity. Adv Cancer Res. 2017;133:1-22. doi: 10.1016/bs.acr.2016.08.001. Epub 2016 Oct 12. PMID: 28052818; PMCID: PMC8341423.

- ↑

Tian Z, Chen S, Shi Y, Wang P, Wu Y, Li G. Dietary advanced glycation end products (dAGEs): An insight between modern diet and health. Food Chem. 2023 Jul 30;415:135735. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2023.135735. Epub 2023 Feb 24. PMID: 36863235.

- ↑

Twarda-Clapa A, Olczak A, Białkowska AM, Koziołkiewicz M. Advanced Glycation End-Products (AGEs): Formation, Chemistry, Classification, Receptors, and Diseases Related to AGEs. Cells. 2022 Apr 12;11(8):1312. doi: 10.3390/cells11081312. PMID: 35455991; PMCID: PMC9029922.

- ↑

Gill V, Kumar V, Singh K, Kumar A, Kim JJ. Advanced Glycation End Products (AGEs) May Be a Striking Link Between Modern Diet and Health. Biomolecules. 2019 Dec 17;9(12):888. doi: 10.3390/biom9120888. PMID: 31861217; PMCID: PMC6995512.

- ↑

Zawada A, Machowiak A, Rychter AM, Ratajczak AE, Szymczak-Tomczak A, Dobrowolska A, Krela-Kaźmierczak I. Accumulation of Advanced Glycation End-Products in the Body and Dietary Habits. Nutrients. 2022 Sep 25;14(19):3982. doi: 10.3390/nu14193982. PMID: 36235635; PMCID: PMC9572209.

- ↑

Dugan B, Conway J, Duggal NA. Inflammaging as a target for healthy ageing. Age Ageing. 2023 Feb 1;52(2):afac328. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afac328. PMID: 36735849.

- ↑

Phuong-Nguyen K, McNeill BA, Aston-Mourney K, Rivera LR. Advanced Glycation End-Products and Their Effects on Gut Health. Nutrients. 2023 Jan 13;15(2):405. doi: 10.3390/nu15020405. PMID: 36678276; PMCID: PMC9867518.

- ↑

Akhter F, Chen D, Akhter A, Sosunov AA, Chen A, McKhann GM, Yan SF, Yan SS. High Dietary Advanced Glycation End Products Impair Mitochondrial and Cognitive Function. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;76(1):165-178. doi: 10.3233/JAD-191236. PMID: 32444539; PMCID: PMC7581068.

Authors

Jinan Banna, PhD, RD

Written by

Jennifer Scheinman, MS, RDN, CDN

Reviewed by